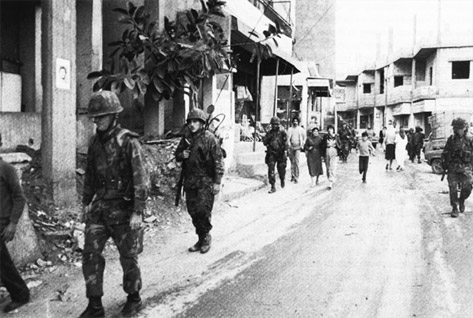

Lebanon 1982-83

U.S. marines patrolling the streets of Beirut

By the mid-1970s, the arrangements worked out for Lebanon after the 1958 intervention – a strengthened army to go along with U.S. economic and political assistance – had been overtaken by demographic changes and a large Palestinian presence. A brutal civil war broke out, ratcheted down to lower levels only when, with U.S. support, the Maronite-dominated regime invited in the Syrians to restore order. The situation remained unchanged through the early 1980s, the U.S. continuing to back the government with various kinds of resource transfers. But in the summer of 1982, Israel , for the second time in four years, invaded Lebanon , advancing toward Beirut and aiming to destroy or at least expel the forces of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO). As Israeli troops moved north, the U.S. , as it had done in similar situations for decades, sent a detachment of marines to evacuate U.S. citizens. Soon after, however, the same marine unit returned as part of an arrranged multinational force (MNF), whose mission was to evacuate the PLO from Beirut and, during that time, to occupy parts of Beirut together with the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF). This mission, which lasted for three weeks, was without incident, as was in fact anticipated by the marine commander, who told reporters, “I am not anticipating any need for us to use our weapons.” 1

Within a week after the marines redeployed to their ships, a series of events, including the assassination of the country's new president and a partly retaliatory massacre of Palestinian refugees, led U.S. policy makers to order the same marine units back to Beirut . Once again they would be part of an MNF, but this time their mandate was twofold: to serve as ”an interposition force” (between whom was not specified) and to “assist” the Lebanese Government and the LAF “in the Beirut area.” Some 1,200 marines (their number would eventually grow to 1,800) thus took up positions around the Beirut airport with extremely restrictive rules of engagement; the thought was that their mere presence would be enough to deter combat anywhere in the area. Soon after the marines had reestablished themselves, the new Lebanon president visited Washington and asked for the MNF to be expanded sufficiently to provide security throughout the country. In light of the large number of non-Lebanese troops outside of Beirut , this was considered a nonstarter unless they could be persuaded to leave peacefully, so the U.S. began negotiations in this direction, while also working “to rebuild the Lebanese security forces” and “improve the Lebanese Government's ability to assume its responsibilities as quickly as possible.” Thus, the marines began training and equipping the LAF while also beginning motorized patrols in Beirut and surrounding areas. The U.S. also arranged an agreement between Lebanon and Israel ending the state of war and providing for Israeli troop withdrawal, contingent on Syrian and Palestinian withdrawal. 2

By the summer of 1983, it was clear that the negotiation and training components of U.S. policy had failed. The U.S. embassy had been bombed in the spring, probably a reaction to (unsuccessful) U.S. pressures on Syria . The LAF remained at a low level of competence (described as “a block of Swiss cheese ... you run into holes in surprising places”) and was seen as incapable of extending control outside of Beirut (in Beirut, it was the MNF which patrolled). Then the marines began to be attacked. The U.S. changed the rules of engagement to permit “aggressive self-defense” (including on behalf of other MNF contingents) and responded by naval bombardment and by launching fighter jets to warn against further escalation. In the meantime, the Israelis had withdrawn from the mountains overlooking Beirut . Although the marine commander proposed occupying those positions, on the grounds that the LAF was incompetent and that Lebanese anti-government forces would avoid ground combat with the U.S., a troop deployment was considered undesirable (both the Europeans and Congress were strongly against) and unnecessary. Instead, Reagan authorized “naval gun fire support and, if deemed necessary, tactical air strikes” in support of LAF operations in the mountains; ordered increased numbers of ships and Marines to the coast of Lebanon (this was described as “a marker for the Syrians”); and intensified diplomatic pressure on Syria . These policies, it was expected, would “force a withdrawal” of enemy “guns and mortars.” As discussed in the book (chapter five), this expectation was grossly inaccurate. 3

1) Quoted in “The Engagement and Disengagement of U.S. Forces From Crises; As the Marines in Beirut Escalate Firepower, Fears Grow That They Are in a Quagmire,” Washington Post , 9 September 1983.

2) Agreement Between the United States and Lebanon , 25 September 1982, quoted in Kelly (1996: 5); Frank (1987: 22, 24, 38-9); Malone, Miller, and Robben (1985: 11); “Next Steps in Lebanon ,” National Security Decision Directive No. 64, 28 October 1982, Federation of American Scientists (2003).

3) Malone, Miller, and Robben (1985: 11, 19); “Strategy for Lebanon ,” National Security Decision Directive 103, 10 September 1983, and Addendum, 11 September 1983, Federation of American Scientists (2003); “Reagan Says Offshore Force is ‘a Marker for the Syrians,'” Washington Post , 5 September 1983; “Fighting in Lebanon : Balance of Forces,” New York Times , 9 September 1983. It is worth noting that the U.S. special envoy to Lebanon pushed for U.S. air and naval support of the LAF on that grounds that otherwise there would be “a serious threat of a decisive military defeat which could involve the fall of the Government of Lebanon within twenty-four hours.” This situation description was not agreed with in Washington , where the Secretary of Defense described it as a “‘sky is falling' cable” (Kelly 1996: 6).